Galicia Jewish Museum: Honoring Jewish life in Poland before and after the Holocaust

Galicia Jewish Museum: Honoring Jewish life in Poland before and after the Holocaust

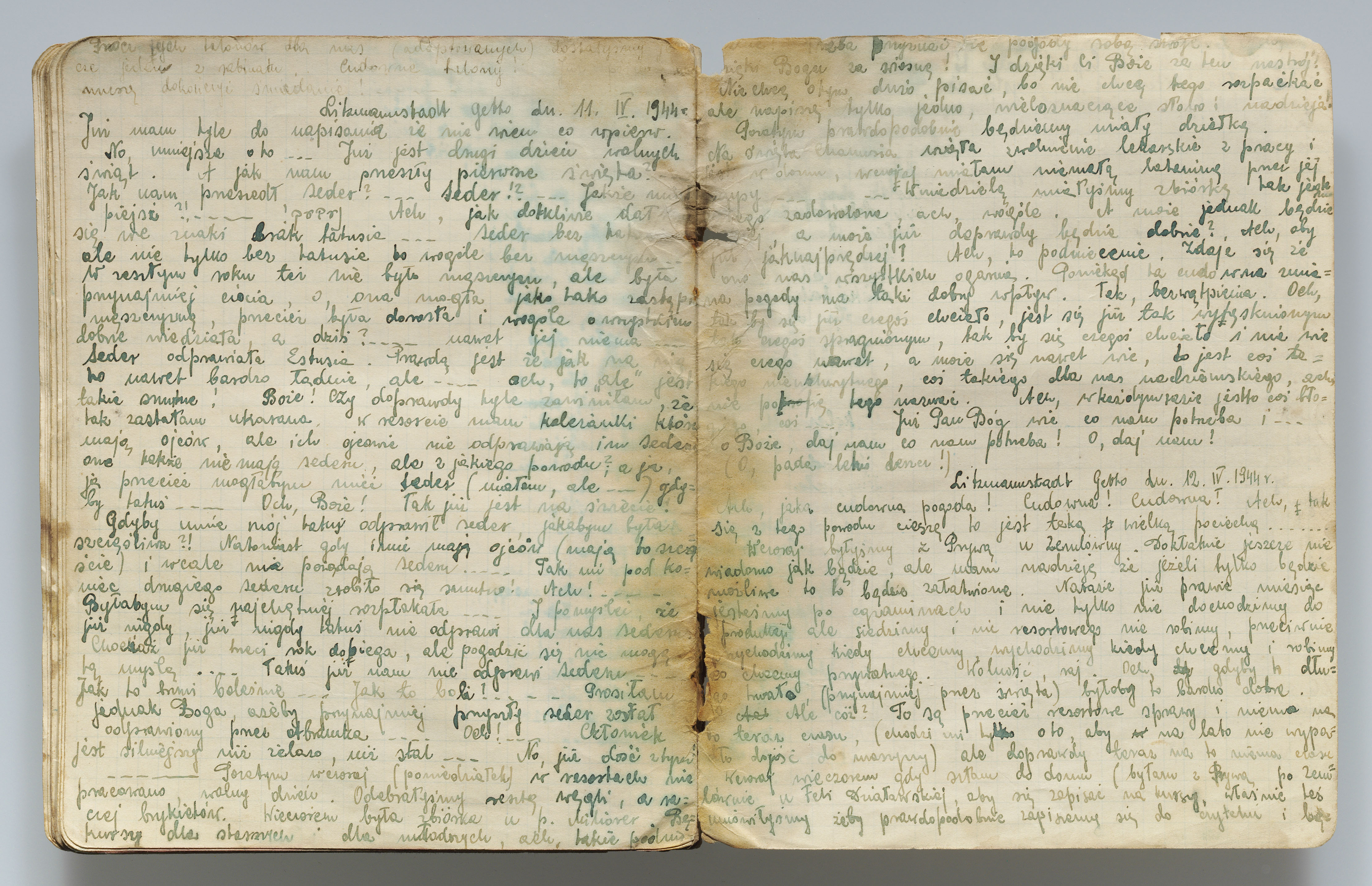

The Galicia Jewish Museum (GJM) opened in Kraków in 2004, as a permanent home for a large collection of contemporary photographs documenting “traces of the Jewish past still visible in the Polish landscape.” The museum quickly evolved to offer additional exhibitions and educational programs, spurring a revival of interest in the country’s Jewish culture. The Koret Foundation has been a supporter of the GJM since 2009 and a champion of the museum’s exhibition based on the diary of Rywka Lipszyc.

Jakub Nowakowski has been the museum’s executive director since 2010. A native Krakowiak, he grew up in the Kazimierz district, where his father’s family—who are not Jewish— has lived for over 150 years. Before the Holocaust, the district had been a center of traditional Jewish life in Kraków for centuries. Pre-war Kazimierz was poor, and non-Jewish families had little interaction with their mostly orthodox and Hasidic Jewish neighbors. Nowakowski comments, “Still, both groups had a significant influence on each other. My mother, who is not Jewish, always called the stove a szabasnik, Yiddish for a Shabbos oven. I grew up thinking this was the proper Polish word for stove.” Today, the Galicia Jewish Museum is a new center of Jewish culture in the Kazimierz district—with global reach and impact through its traveling exhibitions and online content.

Nowakowski points out that “Many foreigners are surprised that the director of the museum is not Jewish. Here in Poland, especially in Kraków, we are so surrounded by Jewishness that people don’t find it unusual. They know that because the Jewish community is so small, many ‘Jewish things’ are being done by non-Jews. I have many non-Jewish friends who are involved in ‘things Jewish.’ These are people who run the Jewish Culture Festival, work in Jewish museums, and are involved in education.”

Nowakowski recently attended the openings of two of the museum’s traveling exhibitions, The Girl in the Diary: Searching for Rywka from the Łódź Ghetto at the Illinois Holocaust Museum in Skokie, and then the opening of Sweet Home Sweet: A Story of Survival, Memory, and Returns at the Holocaust Museum in Los Angeles. These traveling exhibitions play a valuable role in furthering the museum’s mission of bringing stories about Polish-Jewish history to a global audience. We were eager to hear about Sweet Home Sweet, and also to learn more about the museum’s support for Ukrainian refugees over the past year.

A contemporary look at the Jewish past in Poland

The Galicia Jewish Museum, which opened in 2004, is located in the Kazimierz district of Kraków.

KF: How would you describe the purpose of the GJM to your parents and others of their generation, or to younger people who think of the Holocaust as being finished?

Simply put, it is the idea that if not for us, if not us, there would be no other people who would remember the Jewish neighbors. The museum really is dedicated to this idea, that it is primarily a responsibility of the present-day inhabitants to commemorate their former Jewish neighbors. To care for the cemeteries and synagogues. To initiate discussions, to be brave in confronting the past—which was not always glorious. Our permanent exhibition, which is the heart of the museum, is titled Traces of Memory: A Contemporary Look at the Jewish Past in Poland.

KF: The GJM is very attuned to exploring the relationships between Jews and non-Jews in Poland. Why do you think Polish non-Jews had such a different sense of the Holocaust than their Jewish neighbors?

Many people outside Poland have assumed that this is a very antisemitic country, that the Holocaust happened in Poland because Poles cooperated with the Germans. Meanwhile, Poles knew that Jews had been killed in Auschwitz, but the lens through which we would tell the story of the war was far more about ethnic Poles. In our family, we knew about the fate of my grandmother, who was a teenager during the war. She and her sister were arrested on the street in 1942 or 1943. They were sent to a farm in Germany, where they worked as slaves of the Germans. They spent the rest of the war there, and they were abused and raped. One of them came back to Kraków, and that became the story through which our family told the story of the war. Almost every non-Jewish family had a similar experience or second-hand story.

KF: What do you think was your parents’ sense of the Holocaust?

My parents’ generation had very little awareness of the Holocaust. Until the mid-1990s, the Holocaust was not part of the curriculum at school. So, I am part of the first generation that actually was taught—in school, in the ‘90s—about the Holocaust, and we started to understand how different it was from the fate of non-Jewish Poles. This was post-Communist Poland; we were a free and democratic country. I don’t think my mother and her mother would have been interested in the suffering of anyone else, because their own experiences were their filter or focus about the time of the war. The Jews were in there somewhere, but the Jewish story would not have been considered our story.

KF: Most remaining survivors—and liberators—are now quite elderly. If their children or grandchildren come to visit the ‘old country,’ in addition to visiting the Galicia Jewish Museum, the Polin Museum in Warsaw, and so forth, what might they find to tell them about the past?

This is such a timely question, in view of the right-wing government which is once again obsessed with an idea that Jews are coming back to reclaim their possessions, to try to take over things. We want to show that, for the vast majority of these people, these visits are about emotions, about making peace. What they hope for is simply recognition of the past. It’s about honoring the memory of their forebears, and reaching peace of mind.

I think our role—as a museum, and also in a much wider sense, as Poles—is to make sure that whenever they come to Poland, to the small towns and villages where their families lived, they will find the story of their people recognized in some way, with a plaque or memorial, something that acknowledges that those people had been there as our neighbors.

"Sweet Home Sweet: A Story of Survival, Memory, and Returns"

KF: Please tell us about the recent exhibition Sweet Home Sweet and how this story came to the museum.

This exhibition says a lot about the Galicia Jewish Museum. The inspiration for it grew out of our meeting Michelle Ores, who is the daughter of two Holocaust survivors. Her father, Richard Ores, had been confined to the ghetto in Kraków and then imprisoned in Plaszów for almost two years. He was able to bury on the grounds of Plaszów, a pickle jar filled with over a hundred photographs, some that he had taken before the war, of his family and friends, and some that he had taken during the early years of the war, including inside the Kraków ghetto. Shortly after the war, Richard Ores managed to retrieve the jar. His daughter told us all this, and then simply asked, ‘Would you find his collection to be of any interest?’ And, of course, we said, ‘Wow, this is amazing!’

KF: Do these photos provide the storyline of the exhibition?

The story is broad and deep, and psychological as well as visual. Richard’s photographs tell a coherent story of his family, of his generation. We decided to use them as a starting point to make a slightly different exhibition, not focused on the Holocaust survivor, but on the entire family, on Richard’s children and grandchildren. We wanted to explore the relationship of the family to Poland, to the ‘old land.’ It could be Poland or Ukraine, or any place where a family had come from. It is complicated, the ways the second and third generation are influenced by the story of the Holocaust and by having parents and grandparents who are Holocaust survivors. Michelle came to Poland, and made her peace with Poland. We also interviewed other family members, and they provided their own family photos, as well as their own thoughts on contemporary Poland.

We found their stories fascinating, and subtitled the exhibition A Story of Survival, Memory, and Returns. As for the exhibition’s title, Sweet Home Sweet, this is our tribute to Richard Ores. He settled in New Jersey and New York after the war, and he had a successful career as a physician. He would often make some errors while speaking English. And one of those things that his family remembers very well is that instead of ‘Home, sweet home’ he would always say ‘Sweet, home sweet.”

KF: So, it sounds as if Sweet Home Sweet is about the present more than the past…and perhaps about the future.

Exactly. It was fascinating to listen to Richard’s children and grandchildren. We want to understand what Poland represents for them, and what it is that will be left behind after the Holocaust survivors are gone. Documenting survivors is extremely important, but I think it’s time for us to look more at the second and third generations, who have inherited a complicated relationship with Poland, which is a burden. What they will do is very much of interest for us.

KF: Not only has Sweet Home Sweet been designed as a traveling exhibition, but you’ve also created an online version. Please tell us a bit about that.

We hope viewers find sweethomesweet.pl engaging and thought provoking. In addition to showcasing many of Richard’s original photos—from his hidden pickle jar—we scanned many of his later photos, and other pictures from family trips back to Poland, which were numerous. We’ve interspersed illuminating quotes from our interviews with Richard’s children, and we’ve also included two video segments of our interviews. We hope the website might encourage some children and grandchildren of survivors to think differently about Poland, help them want to remember rather than to forget.

Providing a refuge for refugees

KF: Tell us about the museum’s work with Ukrainian refugees.

We became very involved in helping the refugees. We set up a daycare center in March of 2022, and it was open five days a week, providing non-stop activities for the children, including meals, medical and psychological help, as well as all sorts of supplies. We also set up a senior center to help older refugees with language skills, basic computer knowledge, access to health care.

We hired refugees to run and staff the centers. They provided almost all of the programming, including college-level English classes, counseling services, dance classes. We wanted to acknowledge these people’s professional backgrounds, to provide opportunities for them to use their skills and to earn money. We closed the daycare center after 15 months, as mothers who plan to stay here have started sending their children to local schools.

I will add that it has been emotionally difficult to ‘witness’ the refugees’ stories and figure out how we can help them, while keeping the museum on its daily track.

KF: This has been a fascinating conversation for us. Thank you for all your insights. We wish you the best at the Holocaust and Genocide Center in Cape Town.

Thank you for your good wishes and for Koret’s support of the museum’s work— and our growth. Many of the staff have worked here for years, and their experience, knowledge, and devotion are also pillars of our successes. The Galicia Jewish Museum has never been stronger, or more creative, than it is today. The museum will continue producing innovative exhibitions—and I am sure I will find a way to bring the Rywka story to Cape Town and Africa —so I don’t see this as an end to our cooperation, just a change of location.